I’ve read TONS of books, articles, online tutorials, etc. on 3D graphics because of my passion for understanding the 3D graphics pipeline (all the data structures and math that goes into taking 3D models and projecting them as a scene on a 2D computer screen). One of the myriad of calculations that you have to use is called the “dot product”. Every book, article, online tutorial, etc. I’ve ever read says that “in this scenario you use the dot product to calculate this value”, and “In this other (seemingly completely different) scenario, you use the dot product for this other reason”. It’s just been a formula I’ve had to memorize and a list of (seemingly unrelated) scenarios when it should be used.

Well, I got tired of not really understanding what the dot product actually gives us. After years of treating it as a black box, I finally understand what the dot product actually represents. Here’s what I wish someone had told me from the start.

The dot product takes two vectors of n-dimensions and returns a scalar value. Since my interest is 3D graphics, I’ll stick to 3-dimensional vectors. Let’s start with the raw math. How do you calculate the dot product.

Given the two vectors that represent 3D coordinates (x, y, z):

The dot product is calculated like this:

Another way you might see calculated is:

where means the magnitude (or length) of and is the angle between and .

There are two primary uses for the dot product (that I’m aware of). The first is related to finding how directly something is aiming/looking at something else. The other is a concept I’m a little less familiar with, projecting one (non unit) vector onto another (unit) vector.

How closely are you looking at me?

The dot product is frequently used to determine how directly something is “looking” at something else, or whether object-B is in object-A’s “field of view”. Is this guard looking at or near the player? Is this surface facing toward or away from the camera? Is this point on a surface directly facing a light or is it angled slightly away from it?

One important thing to note is that last way to calculate . If both and are normalized (unit vectors with a magnitude/length of 1), then just equals . is a number that ranges from -1 to +1. Given two unit-vectors, one pointing in the direction an object is facing, the other pointing in the direction of a 2nd object, ( means it’s a unit-vector) will tell you how much is “looking” at . If is 1, is looking directly at . If it’s we know that is looking about 45° off from . If it’s we know that is looking about 90° off from . If it’s (it’s negative), is somewhere behind where is looking.

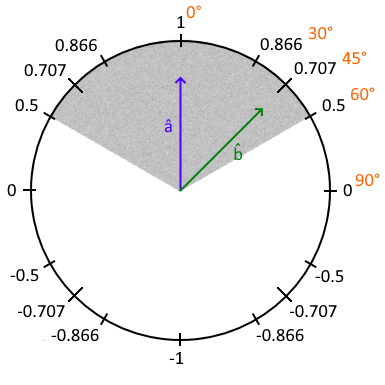

Let’s look at an example. Take a look at the following diagram. is the unit-vector that points in the direction a guard is looking. is the unit vector that points towards the player. (the dot product of and ) will be , meaning that the player is 45° from where the guard is looking. If the guard has a field of view of 120° (60° to either side), indicated by the gray shaded area, then the player is in the guard’s field of view. Probably a bad thing. If, however, was less than 0.5, then the player is greater than 60° from where the guard is looking and is out of the guard’s field of view. If is negative, the player is actually behind the guard.

The exact same calculation is used to determine if a surface is facing toward or away from the camera. This is important because surfaces that are facing away from the camera can be “culled”, meaning they won’t be rendered. This is called Back-Face Culling. It’s the exact same principal as the guard looking at the player scenario, only is the surface normal (a unit-vector pointing straight out of and perpendicular to the surface… aka, what direction the surface is “looking”) and is a unit-vector pointing toward the camera. If is negative, the surface is facing away from the camera and can be culled (excluded from rendering).

Another use of dot product is computing how strong/bright the light is at a point on a surface. Same principal as before, but is the surface normal at that point on the surface, and is a unit-vector pointing at the light source. If is 1, the light is aiming directly at the point and is at its brightest. If it’s between 1 and 0, it’s aiming at an angle and will be progressively dimmer as it approaches 0. If it’s negative, it’s aiming away from the surface and will not provide any light at that point.

One more interesting use of the dot product for determining how directly something is “looking” at something is used in animations. A player walking forward/backward or strafing left/right will have appropriate animations applied to their arms/legs/joints/etc. Let’s say there’s an animation designed for walking forward, one for backwards, one for strafing left, and one for strafing right. If the player is walking forward, obviously the forward animation is applied. But what if they’re walking forward and strafing slightly left at the same time? We need to blend a portion of the forward animation with a portion of the left animation. How much? That’s where our dot product comes into play again. With each animation is a unit-vector defining its direction. Looking at our previous diagram, the forward animation would have a unit-vector pointing straight forward toward 1. The left animation would have a unit-vector pointing left toward 0. To find the portion of each animation to apply, we calculate the dot product of (the direction the player is moving) and each of the animations’ unit-vectors. Any that are negative we ignore. Only the two that is between will be positive. They will indicate what portion of those two animations to blend. Close to 1 means more of that animation. Close to 0 means less of that animation.

Projecting a vector onto another vector

Projecting a vector onto a unit vector is a use that I’m much less familiar with. Hopefully as I type this and research it more, it will become clearer. The essence is that you have a vector pointing to point . You have a unit-vector pointing some direction. You want to know one of two pieces of information:

1. How far along does project? If was an axis extending infinitely, and you looked straight down from the tip of at the axis, where on that axis would project?

2. How far from a plane is point is point ? If the plane is defined by and the plane’s normal vector , how far from the plane is point ?

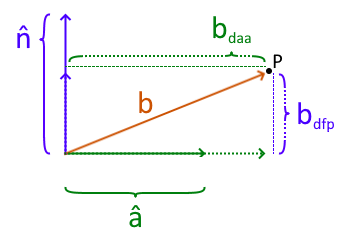

Both of these are calculated using the dot product. Look at the following diagram.

1. How far does (brown/orange vector) project along (solid green unit-vector) is answered with resulting in the magnitude/length of (distance to axis, dotted green vector). This might be used to determine the ground speed of something moving at an angle to the ground (rising or falling).

2. How far a point (black dot) is from a plane defined by the vector and the plane’s normal vector (solid purple unit-vector) is answered creating a vector from the plane’s origin to point , then taking the dot product . This will result in the magnitude/length of (distance from plane, dotted purple vector). This might be used to determine how far above an invisible “kill” plane the player is. If they fall below the “kill” plane, they are killed and respawned.

Summary

The dot product fundamentally measures alignment – whether that’s directional alignment (giving you an angle) or distance alignment (giving you projection length). A dot product of two unit-vectors tells you how directly one is aimed at the other. A dot product of a unit-vector and a target vector tells you how far along the axis defined by the unit-vector the target vector projects. The difference lies in the fact that , and (magnitude of times magnitude of ) results in 1 if they are both unit vectors and you just get . If one of the vectors is not a unit-vector (its magnitude is not necessarily 1), you get that vector’s magnitude/length times .

I hope this helps someone understand dot products and their use in 3D graphics more easily and/or quicker than I. It took until I was 58 before I grasped it enough. And now my (current) understanding of it is documented here so a year from now when I’ve forgotten it all, I can come here and “reload” my memory. 🙂